Part 2: Who’s Doing the most talking? Who’s doing the most thinking?

- Lyn Sharratt

- Apr 24, 2020

- 12 min read

Updated: May 14, 2020

Wonderings

How do we ensure all teachers and leaders know the research about, the impact of, and how to use Accountable Talk across all subject areas?

How do we continue to ensure all voices of leaders, teachers and students are heard when using technology and ‘learning from home’?

Where do we find ‘Knowledgeable Others” who can walk alongside us, coaching and mentoring us, to embed Accountable Talk in practice, that is, in classrooms and in Professional Learning (PL) sessions?

Accountable Talk: A high-impact instructional approach!

Accountable Talk: A High Impact Instructional Approach

Why Accountable Talk? Accountable Talk is an evidence-proven, high-impact instructional approach that not only should be taught but can also be measured through ongoing conversations using an individual, whole-class and small-group format. This paper unpacks that strongly-held belief.

Accountable Talk builds on Oral Language development – so critical in early years’ learning (CLARITY, Chapter 5), and becomes essential in the creation of new knowledge. We learn from others. Learning is a social process. Talk is our single most valuable indicator of thinking, making meaning and understanding in order to assess our own learning and that of our students. Learning to express oneself literately is often difficult enough one-on-one with a teacher or a mentor, without adding the stress of having to express a thought, or to read one’s thoughts to a group of peers without time to think it through and “talk it out” (Sharratt, 2019).

Effective teachers and leaders create communities of conversation with protocols that reduce anxiety and enable students to test out their ideas and their new learning alongside their peers. It causes a ‘deliberate pause’ for us, as leaders, to ask and monitor, “Who is doing the most thinking and the most talking in our classrooms and in our PL conversations?” Student-talk in classrooms and teacher-talk in learning sessions must tip the scales and outweigh teacher or leaders talking-at learners in their care.

Reading and writing, and presenting a point of view, verbally, must always begin with talking about one’s thinking with someone else, such as a ‘talk partner’. Learners, from young learners to graduate students and adult Professional Learning (PL) participants, appreciate the opportunity for oral rehearsal first before being called upon to answer.

Accountable Talk is a data collection tool for classroom teachers: “What do my students know?”; “What do they need to know next?”; “What do I need to know to move my students forward?” Accountable Talk is a learning tool for students who ask: “What do I know?”; “What do I want to learn?”; “How will I learn it?”; “Who can I talk to in order to clarify and extend my thinking?”. In parallel, these are certainly the questions that leaders ask when planning staff PL sessions.

In this paper, I unpack what Accountable Talk is; offer a strong research base of evidence that recommends using it; describe the practical application of Accountable Talk in the classroom with students and during Professional Learning (PL) sessions for teachers and leaders together; and, in conclusion, consider what Accountable Talk looks like in an online environment.

What is Accountable Talk?

The term "Accountable Talk" in classrooms refers to talk that is meaningful, respectful, and mutually beneficial to both speaker and listener. Accountable Talk stimulates higher-order thinking - helping students to learn, reflect on their learning, and communicate their knowledge and understanding. To promote Accountable Talk, teachers create a collaborative learning environment (The Third Teacher, CLARITY, Chapter 1) in which students feel confident in expressing their ideas, opinions, and knowledge (A Guide to Effective Literacy instruction, Volume I Grades 4 - 6).

Accountable Talk Has a Strong Research Base

Accountable Talk as a critical way to bring learners’ voices into focus is steeped in research. The following are some of research studies available that substantiate the importance of students’ verbalizing their thinking in classrooms.

1. Sharratt, 1996, discusses the four levels of discourse/talk:

Discussion: lowest level and often quick as a decision needs to be made;

Dialogue: higher level because there is no expectation that a decision must be made so conversation flows more easily;

Reflection: very high level as more time is taken to not only retell your thinking but also relate it to what has already occurred. Conversation then ends with reflection on what is possible;

Silence: is often an indicator that ideas are being formulated, making meaning is being investigated, and new knowledge is being created. This is when teachers must resist in rushing-in and rescuing a student. Wait-time is a virtue. It is ok to let students struggle and talk it through before expecting a ‘correct’ answer as that struggle is often the very best time for our brains to be working. Teachers need to be attuned to silence and determine why students are being silent – is it that they are thinking or not understanding or disengaged?

2. The research of Michaels, O'Conner and Resnick (2007) about academically productive classroom talk suggests that the critical features of classroom talk fall under three broad dimensions: accountability to the learning community, accountability to the knowledge, and accountability to accepted standards of reasoning. For example:

Accountable to the Learning Community

This is talk that attends seriously to and builds on the ideas of others; participants listen carefully to one another, build on each other's ideas, and ask each other questions aimed at clarifying or expanding a proposition.

Accountable to the Knowledge

This is talk that is accountable to knowledge is based explicitly on facts, written texts or other publicly accessible information that all individuals can access. Students make an effort to get their facts right and make explicit the evidence behind their claims or explanation.

Accountable to the Accepted Standards of Reasoning (Rigorous Thinking)

This is talk that emphasizes logical connections and the drawing of reasonable conclusions. It is talk that involves explanation and self-correction. It often involves searching for premises, rather than simply supporting or attacking conclusions.

3. Mathieson et al. (2007) propose that in order to create a learning environment that builds learning power, a teacher must create positive interpersonal relationships, honor student voice, and encourage perspective-taking. Similarly, teachers can also nurture Accountable Talk by fostering a culture of learning and promoting an ‘open-to-learning’ stance in the classroom where all responses are accepted, all students are respected, and mistakes are treated as rich opportunities for learning (Sharratt, 2019).

4. Lucy West (2012) states that only when you make students’ thinking visible, can you hear what they are thinking and give accurate feedback. That's how it is possible to give verbal descriptive feedback every day to a number of students because you listen to what they are thinking and then can respond immediately with relevant feedback.

5. A research monograph produced by the Ontario Ministry of Education, in 2011 summarizes many research studies by stating, “ When teachers open up a conversation that allows students to take the lead, the classroom becomes a place where learning from one another is the norm, not the exception. Involving students in collaborative structures and teaching students how to engage in meaningful conversations … makes a difference in student learning and achievement, supporting the development of the higher-order thinking skills which are so critical to today’s learners.”

Professional Learning for Teachers and Leaders Models ‘Accountable Talk Moves’ in Classrooms

Professional Learning for teachers and leaders must reflect what good classroom practice is. By co-constructing operating norms and modeling what Accountable Talk looks and sounds like for speakers, listeners, and responders, teachers serve the instrumental role of creating and establishing the ‘Third Teacher’ or a culture of learning in every classroom. Some key ‘Talk Moves” to ensure ongoing dialogue during every PL session and also in every classroom follow.

1. Co-construct Operating Norms

Every PL session must mirror what we expect to see as quality teaching in classrooms. For example, Operating Norms that are established for PL sessions would be similar to those that teachers and students would co-construct. In studying Accountable Talk, we would expect to develop the following Operating Norms:

Listening to others

Hearing every voice

Building on the thoughts of others

Disagreeing agreeably

Practicing sentence stems, such as: “I agree with Dr. Johnston and would add…”; I disagree with what Dr. Johnston is saying because…”; Based on my evidence, I think…”; I can clarify what I mean by …”

Encouraging others

We benefit from the strengths of all when we encourage peers to contribute their thinking in our learning communities. In focusing on Accountable Talk, we must use Operating Norms and refer to them often in order to establish an environment of safety and trust, not only at PL sessions but also in all classrooms.

2. Establish an “Open-to-Learning Stance”

We invite risk-taking, participation and inquiry when we invite others to share their thinking by proposing they “say more about that.” For example, teachers and leaders in all learning-focused sessions use and model

attentive listening,

think alouds,

participation prompts,

leading conversations,

justifications of proposals and challenges.

Teachers and leaders have learners practice these strategies, so they know how to own and present their own thoughts and how to reflect on and respond graciously to the thoughts presented by their peers. This is ‘Accountable Talk-in-Action’.

3. Model Attentive Listening

Listening is an active meaning-making process that requires explicit instruction, time, practice and commitment. Teachers need time to sit alongside students to listen in to their thinking in order to understand where they are and then, to help them to clarify their thoughts. Monitoring our own ability to listen, contribute and build on ideas rather than impatiently waiting for our turn to speak is critical to exposing and supporting student thinking (T. Meikle, Blog, 2014).

4. Commit to Assessment ‘for’ and ‘as’ Learning

Developing understanding of the Assessment Waterfall Chart (below, and in CLARITY, Chapter 5) provides another opportunity to embrace Accountable Talk. Through co-constructing meaning of every component part, everyone learns and through their verbal input demonstrates they are learning the meaning of every step of the waterfall.. This is a process not only with students, but also with teachers when co-planning units or lessons – the work with teachers should of course, be first.

A substantial portion of instructional time must involve students in talking that is related to developing concepts, big ideas, and essential questions that surround the Assessment Waterfall Chart above (CLARITY, Chapter 5, Figure 5.2). To do this, teachers use the powerful Accountable Talk approach. Within that approach, are many instructional strategies as I elaborate on in the next section.

Practical Application of Accountable Talk in Classroom Practice

Many instructional strategies reflect the Accountable Talk approach in classrooms. The monograph “Having Grand Conversations” (PDF attached) elaborates on many Accountable Talk strategies to be heard in K-12 classrooms in every subject area. The following are a few of the most powerful:

1. Allow Think Time/Wait Time

Research conducted on the pacing of questions shows the average amount of time a teacher waits between posing a question and eliciting a response (think time) is less than one second (Rowe, 1986). This must increase in order for students to talk about what they think to another student before being called on to answer. With only one-second wait time, students’ answers were very short (5 seconds on average) and less than 3 words 70% of the time. (Alexander, 2001). The addition of a minimum of 3 seconds of "think time" has been shown to improve the quality of student responses and learning. (refer to Questioning Viewer Guide Learning Video Series www.edugains.ca).

2. Use Think- Pair- Share and Turn and Talk

Think-Pair-Share and Turn and Talk are designed to promote and support higher-order thinking. The teacher asks students to think about a specific topic, pair with another student to discuss their thinking, and then share their ideas with the group. Don't give students too much time for the sharing or they may go off topic or lose interest. You want to give enough time, however, to allow for in-depth conversation. Professional judgement and careful observation needed here. To increase individual accountability and to increase student confidence you could also have students write or diagram their answers after thinking and before sharing (Questioning Viewer Guide Learning Video Series www.edugains.ca).

3. Encourage Student-Designed Higher-Order Thinking (HOT) Questions

University of Melbourne researcher, Dr. Janet Clinton, found that, on average, teachers asked about 200 questions per day and students asked two questions per student per week. The part that may be even more disturbing? Our high-achieving students are OK with this, because they can weed through what is important and what is not. Our struggling students, on the other hand, want the teacher to stop so they can talk it out with a peer who can explain it to them in more student-friendly language (DeWitt, 2020).

Strategies like the use of a Q-chart (see photo below), KWL chart (We Know – We Wonder – We Learned), or a display of ‘Question Starters’ help students generate questions that make them active participants in Learning Conversations.

4. Create Rich Tasks

In order for the students to begin using Accountable Talk there must be interesting, complex ideas and rich tasks to talk and argue about which require teachers to move away from simple questions and one-word answers to problems that support multiple positions or solution paths. (Michaels, O'Conner and Resnick, 2007). Rich tasks build on a knowledge framework and ask students to consider what the task is asking, how to solve the task, what strategies to use, what processes are needed, and how to explain their reasoning (West, 201I). In Chapter 5, CLARITY, Figure 5.12 displays questions teachers ask themselves when planning a rich task for students.

Rich tasks demand Accountable Talk through partner- and small group- sharing in a risk-free learning environment.

5. Co-Planning, Co-Teaching, Co-Debriefing, Co-Reflecting (The 4 C’s Model)

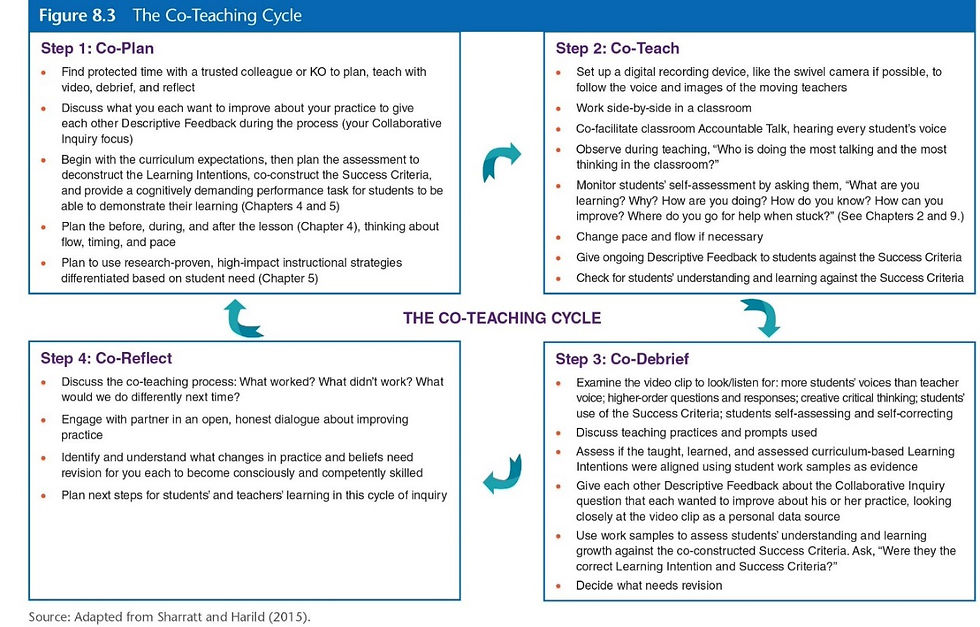

The rich-task methodology for Knowledgeable Others working with teachers, The Co-teaching Cycle, that we refer to as the 4 C’s (Sharratt & Fullan, 2009; Sharratt & Harild, 2015, Sharratt & Planche, 2016), is most effective when they have time ,during the school day, to engage in Accountable Talk, themselves, while using the 4 C’s cycle to explore ‘precision-in-practice in all K-12 classrooms. The detailed 4 C’s process for this is shared in graphic 8.3 below and in CLARITY, 2019, Chapter 8 and, although not explicit, demands Accountable Talk Moves at every step.

What can make the 4C’s model even more effective is to concentrate on the elements of Accountable Talk within the new practice to be trialed. By including a focus on Accountable Talk in the 4C’s plan, student reaction is intensified and clarified resulting in increased levels of students’ interaction and feedback to co-taught lessons.

6. Even More!

Additional Accountable Talk strategies that are detailed in the ‘Having Grand Conversations’ Monograph (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2011) include:

panel discussions;

literature circles;

case study exploration,

presentations, interviews, debates,

inside-outside circles,

fishbowl, and

‘Say Something’

Changing up the Accountable Talk strategies stretches thinking and allows receptivity to be measured and monitored to ensure learners’ knowledge-building. Accountable Talk makes learning ‘come alive’ and allows the classroom, anywhere and at any time, to be a fun and interesting place for students and teachers.

How Does Accountable Talk Apply to Online Teaching?

Students’ voices must be heard more than teachers’ voices no matter what the communication vehicle. Online learning does not preclude quality teaching. Collecting ongoing assessment data to inform instructional strategies for individual students, small groups and whole class instruction is a ‘must do’ wherever, and however the teaching or Professional Learning takes place.

Current leading technology providers offer cues for users to ensure Accountable Talk and safety of participants on platforms (e.g. ZOOM).

Teachers/leaders in classrooms or attending PL sessions must become ‘evident-based’ facilitators who, by listening attentively, manage the time for talk, the quality of the talk, and the opportunities for every voice to be heard. For example, they share with colleagues, online or in-person. Knowledgeable Others, leaders and teachers teach each other how to develop co-constructed Success Criteria with students online, using strong and weak examples of expected tasks. The result is ‘precision-in-practice’ as the photo below shows. By sharing the screens with students and having them come up with the planned, expected Success Criteria for task completion, teachers and students co-construct meaning. By using the white board tool, found in ZOOM for example, they record their thoughts and reflect together on what success looks like and what might be each student’s next steps and goals.

Below is using the Sharing Screen feature and White Board tool, using a screen shot from one of my ZOOM meetings:

Giving Descriptive Feedback will be with individual students or in small groups unless the platform can handle a whole group experience which I refer to as “collective descriptive feedback” (CLARITY, Chapter 5). Peer- and Self-Assessment and Individual Goal setting are easily done using the same online tools of a shared screen and using the white board tool for example in ZOOM however in smaller groups or one-on-one sessions.

Tips for teachers and leaders (Retrieved from Twitter, source unknown) using online communication for ‘Learning-At-Home’ may include:

Accountable Talk must be planned and implemented with the deep understanding that every voice matters in every classroom whether it is online or face-to-face teaching and learning. I believe, as many do, that online learning, even using the Accountable Talk approach, cannot replace in-person, human interaction. Instead, online learning can serve and (when done well) does serve as a bridge between life experiences: the virtual versus the “real deal” of ‘being there’ as teachers. The pressure of having to immediately transport ourselves as educators between these two experiences, because of the impact of COVID-19, has been dramatic and stressful for all us if we are totally honest with each other. And, we can be totally honest if we have set the stage for Accountable Talk, online, between ourselves and our colleagues, between ourselves and our students, and between ourselves and their parents.

It is in a culture of learning that we learn from each other, through Accountable Talk. New knowledge is built together so that all learners flourish. This is the goal. Learning that leads to critical thinking (the complex interaction of skills, resources, and ‘thinking aloud’) propels students, teachers and leaders to think creatively and reflectively. In moving toward this goal, learning in any setting must be scaffolded so that learning is progressive, engaging and empowering. The more we talk, the more we learn, and the more we learn, the more we achieve.

Commitment

I commit to:

Understanding the research that points to the power of Accountable Talk being a pillar of quality teaching in every classroom.

Investigating what works best in our classrooms.

Understanding that Accountable Talk Moves must be well-planned and thoughtfully executed.

Working alongside others to co-plan, co-teach, co-debrief and co-reflect to embed Accountable Talk in our Unit and Lesson Plans.

Giving it ‘a go’!

References

DeWitt, P. (April 2020). AEL, Volume 42, Issue 1. Sydney, Au: Australian Council for Educational Leadership.

Meikle, T. (2016) Blog Post: Making Thinking Audible – A Whole School Approach. Toronto Canada: www.thelearningexchange.ca

Michaels, S., O’Conner, C. and Resnick, L. (2007). Deliberative discourse idealized and realized: accountable talk in the classroom and civic life. Springer Science + Business media 2007.

Ontario Ministry of Education, Canada - Resources website: www.edugains.ca

Ontario Ministry of Education (2011). Having Grand Conversation in Every Classroom.

Toronto, Canada: Queen’s Printer.

Ontario Ministry of Education (2011). Questioning Viewer Guide Learning Video

Series www.edugains.ca). Toronto, Canada: Queen’s Printer.

Ontario Ministry of Education (2003). A Guide to Effective Literacy instruction,

Volume I Grades 4 - 6). Toronto, Canada: Queen’s Printer.

Sharratt, L. (2019). CLARITY: What Matters MOST in Learning, Teaching and

Leading. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Sharratt, L. & Planche, B. (2016). Leading Collaborative Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Corwin.

Sharratt, L. & Harild, G. (2015). Good to Great to Innovate: recalculating the Route, K-12. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Sharratt, L. & Fullan, M. (2009). Realization: The Change Imperative for District-Wide

Reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Sharratt, L. & Fullan, M. (2009). Putting FACES on the Data: What Great Leaders Do!

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

West, Lucy (2011). https://prezi.com/yogggvuqm4on/accountable-talk-in-the-classroom

West, Lucy (2012). www.thelearningexchange.ca/?s=Lucy+West

Appendix

“Having Grand Conversations in the Classroom”

Comments